Thelma Rosner was born in Toronto in 1941 and is currently based in London, Ontario.

Rosner studied at the University of Toronto and the Ontario College of Education between 1959 and 1964. In 1972, she returned to school to study visual art at Western University, in London. Serendipitously, this was the same year that Paterson Ewen joined the faculty at Western. Already showing an interest in exploring issues of ornamentation, Rosner found Ewen to be supportive of the type of work she was making despite the fact that it did not follow art trends of the moment. After leaving Western in 1977, Rosner was faced with the challenge of balancing her studio practice with motherhood and domestic responsibilities.

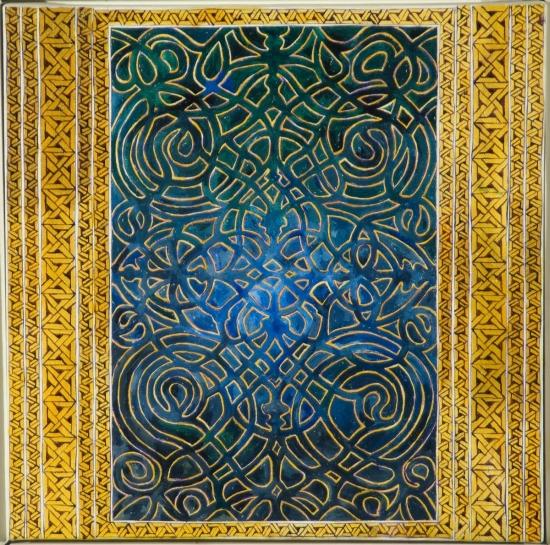

In 1978, Rosner spent a year in Boulder, Colorado, where she encountered the collective, Front Range Women in the Arts, who helped her to strengthen her own personal and professional identities. During this same period, Rosner also had the good fortune to meet George Woodman, a professor at the University of Colorado at Boulder, who validated her interests by helping her to situate her work within the historical origins of pattern and decoration. Over the course of the 1980s, Rosner’s work shifted away from such decorative textual sources as the Book of Kells and Islamic illuminations to embrace other explorations of colour, texture, and structure through gestural, abstract painting.

Rosner’s practice during 1990s was characterized by large-scale paintings that combined abstraction with both high realism and the decorative, juxtaposing renderings of textiles, allusions to the familiarity of female domestic life, and imagery appropriated from the canon of male-dominated western art. Her 1995 exhibition, Collected Stories, presented multi-panel canvases that combined these images to create new, readable narratives of female experience. In 1999, she expanded on these themes in her exhibition Still Life, which also heralded a shift beyond the two-dimensional canvas toward installation. Here, Rosner explored the social resonance of food as a part of domestic life, both broadly within our social and cultural fabric and specifically within Jewish culture. Rosner’s work, Still Life With Her Recipes for example, referred to the ability of food, as well as the ephemera generated by and surrounding food, to embody cultural memory.

More recently, Rosner has expanded her examination of the domestic to include a broader conception of home. The exhibition Homeland (2013) focused on the notion of home in relation to how the concept of native soil – “owned, shared, contested and beloved” – both underlies and undermines the feeling of belonging. This body of work explored the tensions between the Palestinian and Israeli communities – where conflict has been the defining feature of lived existence – by focusing on cultural similarities between the two communities, suggested through images of native flora, cuisine, desire for a stable homeland, and cultural behaviours such as hospitality.

She has exhibited widely across Ontario, at such galleries as Museum London, McIntosh Gallery (London), Justina M. Barnicke Gallery (Toronto), Burlington Art Centre, Art Gallery of Peterborough, Robert McLaughlin Gallery (Oshawa), and McMaster University Art Gallery (Hamilton). Her work is held in numerous public collections including the Canada Council Art Bank, Museum London, London Board of Education, McIntosh Gallery Western University, John Labatt Ltd., and London Life Insurance. She is the recipient of grants from the Ontario Arts Council and Canada Council for the Arts.

Biography by Helen Gregory

SOURCES

Thelma Rosner: Still Life. London Regional and Historical Museums, 1999. Exhibition catalogue.

Thelma Rosner: Collected Stories. Woodstock, Ontario: The Woodstock Art Gallery, 1995. Exhibition catalogue.

Thelma Rosner: Homeland. London, Ontario: Museum London; Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster Museum of Art, McMaster University, 2012. Exhibition catalogue.

The subjects of my work and the materials used have evolved over the decades of my practice, but there are some consistencies. My work often relates to the traditions of Still Life. It is usually structured in a grid, (sometimes obvious, sometimes not), and there are usually elements of pattern and decoration in my presentation. (These characteristics are often associated with the work of women artists.)

My subjects are taken from my concerns as an artist living in the world. They can be as close to me as my kitchen, and as distant as the politics of the Middle East.

Artist’s Statement Courtesy of Thelma Rosner

A Portrait of Thelma Rosner by Madeline Lennon

Thelma Rosner’s art is, in many respects, an intellectual self-portrait. Her paintings reflect an intense and intelligent engagement with literature, with historical situations, and with challenging current political realities. On the other hand, her works also present complex meditations on women’s lives, tracing feminist awareness of their limits and possibilities.

The poet Molly Peacock described the artist as “a thinking sensualist.”* This seems exactly right. Several different series of paintings take beautifully painted food items as the apparent subject. For example, the seven panels of Andalusia (2001-2002) are brilliantly coloured and patterned settings for still life representations of fruits and vegetables depicted at the centre of each panel. Rosner here evokes the medieval period in Spanish history when different cultural groups lived in peace – Christian, Jewish and Muslim people – in contrast with the conflicts experienced later. The abstract red and gold decorative patterns recall Spanish architectural detail of the period. Along the top and bottom of each panel, Arabic and Hebrew names identify the pictured foods, a parallel that reappears in a number of works, such as Arab/Palestinian Dictionary (2009-2011). The importance of food as a significant cultural marker shared by the two groups suggests the potential for an enriched life when cultures co-exist positively.

References to women’s work appear throughout Rosner’s production: food preparation, quilting, rug weaving, and even diapering (Soak Stain Piece, 1977). Her constructions are often based on a grid, strictly or loosely fashioned, informing the overall impression of a given painting. This is the case for early works such as Housework (1978) and Celtic Series (1979-1981), and more recent paintings like Cross-Stitch (2011-2012). However, to describe the paintings in the Cross-Stitch series as based on a grid is much too simplistic given the artist’s complex techniques. In this case, she began by pouring paint across a large canvas and then worked through the vivid colours with strokes mimicking the embroidered cross-stitch. Although the references are to traditional women’s work of making rugs and needlepoint, the images she embeds in the designs are jet planes, rockets, helicopters, flowers, houses, boats, bombs, machine guns – evoking a complicated contemporary existence. Beauty and terror combine in these entrancing large-scale paintings.

How to characterize the artistic production of Thelma Rosner? Consistently strong and challenging, her paintings and prints provoke a viewer to look more deeply to decipher the images and constructions. The sheer beauty of the painting, the obvious care with which it is created, draws us in, and then it is up to us to work out the message the artist has embedded there.

Let me close this tribute on a personal note. One of my favourite Thelma Rosner paintings is She is lost forever (1992), one of a group of paintings dedicated specifically to female experience, and referencing literature by women authors. In this case, the title is a quotation from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. This is a spectacular painting in the form of a triptych, three panels that play together and with brilliant colours, especially red. In the centre, arranged vertically, are three related representations: a detail of an oriental carpet; the cropped (headless) figure of a woman whose costume suggests the Elizabethan queen holding a prayer book; and a detail of the medieval Unicorn tapestry. Here we have a representation of chastity (despite the suggestive thrust of the unicorn horn upward toward the ‘virgin queen’). In contrast, the two large side panels of this triptych are loose abstractions, sensual, colourful and suggestive of passionate abandon. Even if one did not ‘get’ the specific references to the medieval tapestry or the costumed woman, the contrast between the tightly constricted (and meticulously painted) centre panels, and the wildness of the flanking panels, the idea of patriarchal domination and restriction of the female as opposed to the internal desires of women, is a loud trumpet call.

*Molly Peacock, “Thelma Rosner: a thinking sensualist”, in Seen and Unseen. Marion Drysdale, Thelma Rosner, Gerald Vaandering (McIntosh Gallery, 2003), n.p.

See also: Diana C. Coates; Madeline Lennon

CV Courtesy of Thelma Rosner

Biography Profile Photo Courtesy of Thelma Rosner

A Driving Force interview conducted by Paige Linner

M.A. Public History Program, Western University

Eric Simard, Videographer

_______________________________________

Click here for information about works by Thelma Rosner

Click here for information about works by Thelma Rosner

in McIntosh Gallery’s collection.

Curriculum Vitae

Video Gallery

Play Video

Play Video A Driving Force Interview: Thelma Rosner